With the temperature dropping, it's time to find someone to keep you warm. Find your hookups with our online dating guide!

With the temperature dropping, it's time to find someone to keep you warm. Find your hookups with our online dating guide!

Interview date: 02/21/2008

Run date: 04/04/2008

Music Home / Entertainment Channel / Bullz-Eye Home

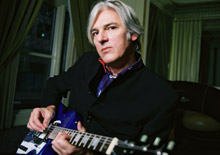

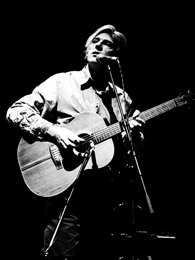

When we last checked in with Robyn Hitchcock, he was busy promoting Ole Tarantula, his debut album with The Venus 3. Since then, he's kept the folks at his label (Yep Roc) hopping by having them begin a massive reissue campaign for his back catalog. Now, he's talking up a documentary entitled "Sex, Food, Death…and Insects", released through A&E Home Video, which takes viewers on a trip through a recording session with Hitchcock and the cast of assorted characters who tend to fall into his gravitational pull these days. The punchline? We may never actually get an album containing the songs recorded within this session. In addition to offering an explanation for this depressing revelation, Hitchcock also discusses his work with Captain Sensible from once upon a long ago, considers why I Often Dream of Trains has suddenly become his signature album, and clarifies exactly what's so great about cheese.

Robyn Hitchcock: Hi, there.

Bullz-Eye: Hey, Robyn, how's it going?

RH: Fine. Where are you?

BE: I'm in Norfolk, Virginia.

RH: Norfolk, Virginia…

BE: Yeah, we spoke about…a year and a half ago, I guess. I live right around the corner from The Boathouse.

RH: Oh, right, okay. Is it still there?

BE: The majority of it is, but it got wounded it a hurricane a few years back and they've never bothered to repair it, unfortunately.

RH: So they don't have gigs there anymore?

BE: No, sadly.

RH: Well, I think it's nearly 20 years since I played there, actually.

BE: Yeah, actually, it probably is. I think I saw you there in '89.

RH: Right, oh, wow! So…are you Will, then?

BE: I am Will, yes.

RH: Okay. So, what did we discuss last time?

BE: Last time, your album with the Venus 3 had just come out, and I praised it to the rafters.

RH: Oh, okay, Ole Tarantula.

BE: Yes, exactly. And now we're talking about "Sex, Food, Death…and Insects."

RH: Right, okay.

BE: That's the documentary as opposed to the individual items. I presume the special came about because of…well, I guess I should say that it's at least not just coincidental that you had worked with (director) John Edginton on "The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story" already.

RH: That's right. That's where we met, and we seemed to get along well, and he came to see me in New York and decided he would like to do something. So we stayed in touch, and eventually he mustered the backing for the documentary. At the same time, we…as you know from our previous conversation, the Venus 3 had evolved as my new band, and we decided to record here in the house, because there's just enough room. I live in London, but the house is just far enough away from everybody for us to be able to record in it without people complaining, and so we did, and they filmed it.

RH: That's right. That's where we met, and we seemed to get along well, and he came to see me in New York and decided he would like to do something. So we stayed in touch, and eventually he mustered the backing for the documentary. At the same time, we…as you know from our previous conversation, the Venus 3 had evolved as my new band, and we decided to record here in the house, because there's just enough room. I live in London, but the house is just far enough away from everybody for us to be able to record in it without people complaining, and so we did, and they filmed it.

BE: And Sundance picked it up to show it.

RH: Well, Sundance actually sponsored it. I think the BBC put in a little bit of money, but the bulk of it was from Sundance. I guess they commissioned John to do it and then it's now coming out on video.

BE: Yes. Actually, until I saw the John Edginton connection, I was first wondering if there was an obsessive Hitchcock fan at Sundance who was just giddy to give you some exposure.

RH: Well, there's people bossing around the place who are into my stuff. I mean, they're probably now quite high up in government, some of them, but probably most of them aren't going to trouble me. But, you know, there are kind of…sleepers stashed here and there who help out, which is nice.

BE: John Paul Jones (late of Led Zeppelin) just seems like the most laidback, ordinary guy…which strikes me as weird, just because I think of him in terms of him being a rock legend.

RH: Well, I would never dignify him with the epitaph "ordinary," but I admit that he resonates with himself below the surface so you don't really know what's going on, and I think he's always been like that. I mean, he's had many incarnations, you know. He was around for quite a long time before Led Zeppelin struck and was actually a very respected session musician. His parents were theatrical performers, and he was actually making a living as an arranger and a bass player from the age of about 16. That's kind of extraordinary. I think he was actually on the scene in London before the Beatles.

BE: Wow. I knew he'd been around, but I didn't realize it was quite that long.

RH: Yeah, so I guess he knew Jimmy Page…well, I know he knew Jimmy Page, who was another respected session man, and then Led Zeppelin occurred and nothing was the same again. Now John is basically a Bluegrass player; he's just producing one of the members of Nickel Creek at the moment. He did Uncle Earl last year. Have you heard that album?

BE: No, not yet.

RH: Oh, it's fantastic. It's got Gillian Welch playing drums on it.

BE: Oh, excellent.

RH: They're a wonderful bunch of girls. But, yes, he plays with me sometimes, and we're actually playing in Norway in the end of April; we've got a gig out there. He does all sorts of stuff.

BE: How did you and he cross paths originally?

RH: Well, he was local; he's a W4 guy, you know, West London, same as Nick Lowe. I mean, I met Nick years ago, but I re-met him in the cheese shop, the local one, and we gradually started to see more of each other. That's why Nick and John both appear in the film, and I guess they must run into each other from time to time.

BE: What is it about you and cheese? There was a discussion about cheese on the tour van at one point, also.

RH: Well it's kind of toxic but lovely. You know, cheese is the opiate of food stuff. I suppose it's kind of as bad for you in its own sweet way as the sort of drugs that I'm now way too old to take. You know, drugs are for kids, anyway. I don't know, I mean, even cheese is now…we don't really keep it in the household. It's just a bit of a treat. I think it's just very full, fat, and it's got fungus in it, and it's a sort of part-living organism that we eat. But, anyway, I'm a big fan of certain cheeses, yeah.

BE: You were mentioning Nick Lowe, and you are doing a couple of dates with him in the states.

RH: Well, we are; this is really great. I mean, Nick and I are white-haired Englishmen; I'm like his sort of psychedelic little brother, really, he's three or four years older than me. Again, he's younger than John, but he was around…he started playing professionally, I suppose, at the end of the ‘60's, but he remembers all that mod stuff and things, when I was really just a preteen boy. His sensibility, I suppose, he's another…in a way, musically, he's American, but his head is English, and his head is quite old school English. His dad was in the RAF, you know, Nick is a real old English gentleman in a way. Sort of standing before the fireplace with a glass of sherry and sort of squinting down his monocle, you know.

BE: He is definitely class embodified, I would say.

RH: Well he's classy, you know. We're both refugees from private education and have spent a lifetime in the sort of rock and roll toilet to get away from it. I came along a few years later, so for me, my epiphany was 1967, and I had no idea that things were not going to carry on like that forever. So if you kind of look in my DNA, you'll see Piper at the Gates of Dawn and Are You Experienced and Sgt. Pepper and all that. Nick sort of almost reminds me of…sometimes it sounds a bit like early Elvis, almost.

BE: Oh, absolutely. Especially with his more recent stuff, I would say.

RH: The more recent stuff is kind of…it's a sort of sophisticated, almost effortless lounge music, but not the same way that, say, Bryan Ferry makes it. There's no hint of any sort of chrome; Nick is much more sort of polished wood and velvet.

BE: Laid back because he can afford to be.

RH: Well, it's laid back as he…one thing you do work out as you get older, you work out how to achieve more for less effort. You know, you pump an awful lot into it when you're a kid. I mean, admittedly you've got more stuff to pump, I suppose, especially if you're a young guy. But you learn after awhile that you don't have to make so much effort to achieve what you want to achieve, and I think we've both sort of come to that. I think also Nick and I both probably underplayed ourselves a bit when we were younger as a kind of…perhaps, I mean I'm speaking for him here, but as a reaction to how serious musicians seem to take themselves and perhaps also because of a little bit of a lack of confidence in who we were, you know, in who we both were. So we kind of got this reputation of being wise guys, you know. Maybe we weren't really soulful, we were just a bit of a joke, I mean, in different ways. I think we both kind of have kind of developed; I think we both have kind of found out who we are a bit. Anyway, you'll found out if you come and see us. What is this interview for? Is this online?

BE: Yes, it's for Bullz-Eye.com.

RH: Oh, okay. So it's not to any particular region?

BE: No, it's worldwide.

RH: Oh so they can all read this in Tokyo?

BE: Oh absolutely. If they can read English.

RH: Hello, Tokyo. Hello, Tad. Hello, Koichi. Hello, Yoko.

BE: (laughs) Gillian Welch and Peter Buck give the impression that you're less about schedule and more about spontaneity. Like, the spirit moves you and you're off and running.

RH: Yeah, I like it. I mean, I've never been very patient. I'm not one of those people who says, "Well, we're going to build this bridge, we're going to make this record, and spend three or four months, and at the end, we'll really have something to show for it." I mean, on the occasions where I've had the budget to do that, I don't think the results have been very good. People who like my stuff always seem to like…the quicker and cheaper I do it, the more popular it is. I mean, it's just good to do things quickly. I think Peter's like that, you know, he doesn't want to stand around in a mixing room. He's not going to sit there with what R.E.M. he's made, twiddling the flavors and sitting in the back of the room and stroking his chin. He comes in, he does what he does, and then he's off and then he'll come back in with a new riff. Peter would make a new album every day, I think, if it was left to him.

BE: Well I got that impression from him, with the way he was talking about how R.E.M. gets frustrating for him because they actually want to relax between albums and he just wants to keep working.

RH: Well, he loves to work. During the albums, I think he likes to get it done quickly, and I think the others were kind of, you know, the usual thing of having a big budget and a slight lack of purpose. They just spend a long time needlessly polishing what they have. I think that, with the new album, they really got on with it; from what I've heard of it, it sounds like a follow up to Document.

BE: Oh, excellent!

RH: Have you heard it?

BE: No, I'm very much looking forward to it, especially after that comment.

RH: Well, I think it's a mature version of it, but the feel just reminds me of that, especially watching them play it live. I think they sort of rediscovered themselves as an organic band rather than as a collection of millionaires. That's really good, and I think Peter just likes to…yeah, we like to work quickly. Gillian likes to get on with it, you know. I mean, I think that she and Dave (Rawlings) are very careful about what they do and about the sound. They like to sort of take time, and they own their own studio and, again, they can afford to take time. I just chuck stuff out, you know.

BE: Well, I had to laugh at her comment about how one of the songs that you all recorded together where, on the first take, she didn't even have her instrument in her hand before you'd started playing.

RH: Oh, boy. No, but she picked it up pretty quickly. I mean, I think the tapes were running all the time, I don't know. I don't remember the red light coming on; they just seemed to telepathically know when we were going to start playing. The thing about that stuff is how few count-ins there are. But I also put that down to how she and Dave work and, you know, because there is so much music collectively between them, and I felt like I was sort of tuned in to that. I was the guest. Again, they are very good people to work with quickly.

BE: You were talking about how the most respected stuff is the stuff that cost the least. During the special, there is like a break where you stop talking about the present and all your collaborators start praising I Often Dream of Trains. Now I've been a fan of that album for years, but when did it suddenly start being held up as the gold standard to your discography? It seems like recently everyone has begun praising it very specifically.

RH: I don't know, I mean, that was pretty cheap. The one they used to like was Underwater Moonlight, by the Soft Boys, which I think cost about 600 pounds. Trains cost about 1,100, but it was four years later, so allow for inflation. What they both are is kind of nothing to do with their era. I mean, if you listen to them, you can hear how my voice is younger and everything, but I suppose there's no…I think there's a bit of chorusing on the guitars that might be a bit of a giveaway that it was from the mid ‘80s, but, on the whole. it's…you know, you think of the sounds that they had then, the sort of whole shoulder pads that were there in the music as well; big drums that a plane could take off and land from. Everything was shiny like special toothpaste back then, and I think Trains really isn't. Actually, having said that, R.E.M. weren't, either. I'm sure you can trace the ‘80s through Bill Berry's drum sound a bit, but certainly R.E.M. didn't sound anything like what was going on at the time. Yeah, I mean, I'm really glad people like it. It's good; it's great that people still want to hear those things. And hear them they do, because it's coming out for the third or fourth time, I think.

BE: Yeah, actually, I was going to ask: with the box set, at first it seemed odd that I Often Dream of Trains would be side by side with Eye, but I guess they're almost companion pieces, sonically, even though there are quite a few years between each other.

RH: Yeah, you know, they're in the same medium, that's the thing. I mean, the Egyptians stuff is being packaged…in fact, when you rang, I was just listening to some things I haven't heard in 20 years, and I think there is going to be some really good stuff from the Egyptiansbox set. But to me it made more sense to keep all the Egyptians stuff together and have all the Hitchcock stuff together. It didn't quite fit chronologically, but I think the mood of it fits. And, as you say, you can move from Trains to Eye, and you can look at my psychic landscape changing in the course of that. For me, an awful lot changed. When I recorded and wrote those songs for Trains, I was living a completely hermitic existence. I didn't know if I would ever make a record or tour again. I was just sort of kind of keeping myself alive doing odd jobs and recording just entirely for my own sake; I got a little four track machine. I suppose that was the good thing about Trains: it was motiveless. There was no idea of what a record company will think of this or anything. Whereas when I recorded Eye, I was signed to A&M and I was a little alternative demigod and I had lots of American boys and girls getting excited, you know. It was on MTV and it was a really different world for me. You can sort of see me…one was sort of really marinating in my own reflections and my own preoccupations, I suppose, the Trains record. And Eye is much more instant. It's much more about what has happened to me in that past six months or year. There may be one or two old songs on it, but mostly it was a reaction to my life and affairs at the time, so you got the choice.

BE: Actually, this is kind of a sidebar question that just occurred to me. You talk about doing odd jobs about the time of I Often Dream of Trains, was that the time you were working with Captain Sensible?

RH: (seemingly impressed that I'd made the connection) Indeed! I saw him last week, in fact, and he's looking good. We actually have been doing I Often Dream of Trains as a show. We did it in Britain, at a few gigs, and it seemed to work well, in this day of tributes and performing one's greatest hits or whatever. They said, "Well, why don't you do Trains?" And I went, I have, and Sensible came along. Yeah, I wrote lyrics for him while he was having his A&M pop star phase.

BE: His album that you did most of the songs for is out of print…well, possibly not in Japan…but someone had sent me some MP3s of those collaborations, which I had never heard before, and I really enjoy them.

RH: Oh, it must be one of the few things that isn't available on CD.

BE: Well, I think it has been; I think it's just out of print right now.

RH: Alright. That was some good stuff.

BE: Oh, yeah, I enjoyed what I heard.

RH: I mean, you know, he was doing it from the opposite end; he had absolutely no qualms about it. He had been a punk star and thought, "Oh, well, what the hell; let's make a pop record." I think that never really happens to me so naturally. I love certain pop music, but I've never really felt that comfortable…I don't know, whatever, you know, I do what I do. He just went in and had a number one hit with "Happy Talk," and everybody loved it because he was this punk doing Rodgers and Hammerstein.

BE: You do a mean Johnny Cash impression during the special.

RH: Do I?

BE: Well, it's very brief, but it's where you said you were trying to do a song one way and it came out sounding like Johnny Cash instead.

RH: Oh, well, early in the morning, yeah. I think as the day goes on, it gets harder. I know Grant-Lee Phillips and I have sung Ring of Fire sometimes, but…it's just that he had that tone of voice. Have you seen the movie, the one with Reese Witherspoon?

BE: Oh, "Walk the Line?"

RH: Yeah, "Walk the Line."

BE: Yeah, I enjoyed it. I mean, for what it was, I think it tells a fair amount of the story that a lot of people in the mainstream might not have known.

RH: Yeah, I just felt their performances were great. I sort of forgot they were actors.

BE: Given your appreciation of British folk, are you much of an American country music fan?

RH: I don't know a lot about it, but it's always been around, and it keeps cropping up, right back to when we were in the Portland Arms in Cambridge. Andy Metcalfe was a bluegrass player, I think, when I met him, before he was a bass player. People like Chris Cox, he recorded a lot of my stuff, they were all playing mandolin. Right up to John Paul Jones doing what he does, and Gill and Dave; it's always as a tangent. I always seem to know people who play it, but I don't sort of rush out and put on …it depends on what you mean. If you mean sort of the Luther Brothers or the Stanley Brothers or something, the old things, I mean, Loretta Lynn or Dwight, not the very schmaltzy. It goes from the divine to the inedible, really. But, yeah, I would love to make a country record sometime, actually. I probably have to…it's a question whether I would actually write songs in that idiom or whether I would do like Bob Dylan when he did National Skyline. But he had been working in Nashville for three or four years before he did that. He had those guys playing with him since Blonde on Blonde, it's just that he sort of came over to them in that way. Or whether I would actually take a bunch of old songs and do them with people. I imagine if I did it would be more the bluegrass end of it rather than the kind of schmaltzy end.

BE: How do you go about culling a set list when you have as huge a discography as you do? I mean, do you make a conscious effort to try and mix in material from across the board, or is it just a "let's see what we feel like tonight" kind of situation.

RH: A mixture of the two. I mean, that's one of the things about doing…if I say, okay, we're going to do I Often Dream of Trains, then in a way that makes it much simpler. You just perform I Often Dream of Trains. And I know I made a few editorial changes, I took out a couple of songs and substituted other songs from that era, and I pulled out one song that no one had ever heard that I found on a tape that was an outtake, and then I would do a couple of songs from Eye as an encore. I mean, I could quite happily play…if I played nothing I had written after 1990, most people would be happy. Just because the long-term fans, that's what they remember, and the newer ones probably have heard the older records. But some nights I might play almost entirely recent stuff, especially with The Venus 3. And people don't seem to mind that, either. I mean, I guess it's a bit of a problem, but it's a good problem to have.

RH: A mixture of the two. I mean, that's one of the things about doing…if I say, okay, we're going to do I Often Dream of Trains, then in a way that makes it much simpler. You just perform I Often Dream of Trains. And I know I made a few editorial changes, I took out a couple of songs and substituted other songs from that era, and I pulled out one song that no one had ever heard that I found on a tape that was an outtake, and then I would do a couple of songs from Eye as an encore. I mean, I could quite happily play…if I played nothing I had written after 1990, most people would be happy. Just because the long-term fans, that's what they remember, and the newer ones probably have heard the older records. But some nights I might play almost entirely recent stuff, especially with The Venus 3. And people don't seem to mind that, either. I mean, I guess it's a bit of a problem, but it's a good problem to have.

BE: Have you done any further collaborating with Andy "Two Sheds" Partridge?

RH: Well, yeah, we're about to actually go back in his shed! He had this terrible accident with the headphones: he was listening to the silence in the recording studio, and the cans were up quite loud, and the engineer didn't realize he had the cans on, and he put some tones through it. And Andy was left with a noise in each ear that were like sort of three tones apart. I think it almost killed him, but he's now…he has sort of hearing aids that make him, as he said, trick his ear into thinking he can't hear anything. He sounds quite perky, amazingly, but this happened after we had done something two years ago, and that really put him out of action for a bit. Yeah, I think we are going to do some more.

BE: Excellent. Yeah, I think I maybe talked to him maybe a month after I talked to you last time, so that must have happened immediately thereafter. He was still gearing up for the release of the Monstrance album at the time.

RH: Which album?

BE: Monstrance, the one he did with...I'm blanking on his name, but he's from…

RH: Barry Andrews?

BE: Yes, there you go. I was going to say he's from Shriekback.

RH: Oh, okay. Well, this must have just happened after then, yes. Well, I don't know, we've worked on some songs, and there was one we actually recorded in his shed, which sounded fantastic. Of course, to him it sounds like a demo and to me it sounds like a master. But I think it sounds really good, so we're going to try a bit more, yeah. (Writer's note: checking back, it turns out that Andy actually did mention the incident when we talked, but he did so in such an offhanded manner that I'd forgotten it.)

BE: The last time we talked, I gave you the scoop that Glenn Tilbrook was going to be playing with you on that cruise in Japan, which has long since taken place.

RH: That's right, Glenn was there. I've got a tape of us playing. Yeah, he's good.

BE: I saw the set list, I guess it was about half covers, half your material.

RH: Well we ran through some…yeah, it was informal. I think we did manage to do things like "Band of Gold," but you know, he's another guy who likes to just play, really. Maybe as time goes by you kind of blur your own songs with other people's. You sort of feel, or I do, if there's a song I've known long enough, by somebody else, I sort of feel like it's mine. I mean, I couldn't claim the PRS, but I feel it's been part of me for so long that it effects the way I write. Some of my old songs, I can't remember a time before I had written them. There must have been a time when I hadn't written "Uncorrected Personality Traits" or "My Wife And My Dead Wife" or "Queen Elvis," or whatever, but they seem to kind of follow me around, and they keep me alive, so I'm grateful to them. But then I might equally well do "Big Eyed Beans From Venus" or "Astronomy Domine" or "Baby, You're a Rich Man" or "Waterloo Sunset" or something. I'm sure the internet is crawling with me doing these things.

BE: Oh, it is.

RH: When you meet up with somebody like Glenn…I mean, Glenn actually had hits, so he enters popular mythology at a completely different level from me. I mean, so much goes back upstream to the Beatles. If you put Partridge, Tillbrook, me and, I don't know, Nick, together, I imagine what we'd all wind up doing is singing Beatles songs.

BE: There's a concert I would like to see.

RH: Or debating the chords. "Well, I think it's a flattened 9th here." "Oh, no, no." We're all sort of Beatles nephews and Beatles grandchildren, so it's hardly new is it?

BE: I'm putting together what is essentially an idiot's guide to Robyn Hitchcock for PopDose.com, where I'm writing a bit about each of your albums….

RH: Well, I think idiots generally like my stuff a lot. They're not so prejudiced.

BE: (laughs) Well, I'm trying to avoid the actual use of the word idiot, but…if you had your druthers, which album do you think would warrant the most discussion and the least?

RH: Well, the most discussion, or just the ones I would listen to?

BE: I guess the latter would be the best question.

RH: Oh, God, how many of them there are. The ones that are kind of…that generally, I suppose, are better known, if you like, than others. So people tend to pick from the Soft Boys, they'll pick Underwater Moonlight rather than Can of Bees. Underwater Moonlight is much more listenable, and Can of Bees was no fun to make, but, in some ways, it was probably a more pioneering record. I'm not sure what it pioneered, but…I mean, that stuff is supposed to come out next year. That's a whole other world I don't know. You know, that's right at the beginning. It seems to me like the ones that have monies and time spent on them, like Groovy Decay and PerspexIsland and Respect, on the whole didn't work so well. I think the songs are alright, but I don't think that they're really that great to listen to. I seem to disappear in a sea of reverb and overdubs. Whereas, I suppose, the things that I've been very hands-on about, like I Often Dream of Trains and Eye and Moss Elixir and things are probably closer to me just because I'm closer to them, if you like. I don't know whether the songs are any better. I'm very fond of Spooked because I was so happy to have kind of lured Gill and David into making that. It wasn't planned, I just had a break over there with us doing "The Manchurian Candidate," and they said I could come down for a weekend, and I had the time off, so I did. It then worked so well that I was able to kind of get them to agree to finish it off. They're musicians; they couldn't resist playing. It was so great playing with them. So that's one of my favorites, and I think it's pretty natural sounding. But, you know, they've all got good points. I think my favorite from with the Egyptians is probably Fegmania! but they've all got good things going for them. The Soft Boys reunion album (Nextdoorland) wasn't bad, but the songs weren't as good as Underwater Moonlight. Psychologically, it probably wasn't a good thing for the Soft Boys, per se. It was a bit undead, I felt. I mean, I still do bits and pieces of Morris and Kim, but…it really was a mistake to actually call that. But there's a couple of good songs; Matthew played some good stuff. I'm very happy with most of it, but I haven't heard most of it now. I listen to stuff when it gets reissued or prior to the reissues, so I'll be checking the Egyptian stuff, but then I probably won't hear them again in this lifetime. I don't know.

BE: Is the A&M stuff every going to be reissued? Do they own the masters?

RH: It's out of my hands. I like the first two, I'm not so keen on the second two. We do have some great demos from immediately before and right after the A&M era which will bookend the unreleased…will be kind of the bonus discs in the pack. I think it really shows the span that that outfit was capable of. That's good stuff, too.

BE: And then just the last question. Given how complete the songs sound on the special, when is the album itself coming out that contains those songs?

RH: Well that's a good question. In fact I'm just sending one of those songs off as a part B side. Nick Lowe and I are doing a double sided single on Yep Roc, from our tour; for our three date tour, which will be available from the foyer, and it's vinyl. I think we're going to have one of those songs, and it's actually got Nick singing on the chorus, which is nice. It was great, but I then recorded a load of other stuff the following year because I had written it, and we had the band and everyone…we all like to go. I think both Peter and I would rather record new material than sit around polishing older gems or stones or pieces of music. So what we have is…I've got about 20, well over 20 songs recorded, and I've just got to find out which ones…I don't think that thing will come out, you know. I don't think it will come out. I think pieces of it will come out, but I don't think there are any plans for that record, as such, to come out.

BE: Well, surely you're ready for a sprawling, uneven two-disc affair.

RH: Um, I think some people might be. But I don't think people really welcome double albums. And I don't think they welcome 70-minute CDs. I think that's one of the problems that R.E.M. had: they just couldn't decide which tracks to get rid of, so they just made longer and longer records. In this age where you can hardly give away music, let alone sell it, I think one of the ways to seduce the listener is to present them with a short piece of music. Everything is available, anyway; if you want to download it, you can find it. The record companies are just desperate to give away anything for free to lure people in. Or in my case, everything will come out 20 years later as part of a box set. You have a really good perspective on stuff later. Some of the things we've done…demos we've just finished off, things that I've had 20 years previously…I think we'll make this nice and to the point, the next album, and it will contain elements of the thing we recorded with John Edgington. But the whole thing is just sitting there in the vault; it's monstrous. I mean, not horrible, but there's piles of it. It's like a kind of Let It Be, but with good vibes. There's just cover versions and old things retaken and stuff done at parties and late night things with Nick and John and everybody. It's all fantastic but I don't think that will appear.

RH: Um, I think some people might be. But I don't think people really welcome double albums. And I don't think they welcome 70-minute CDs. I think that's one of the problems that R.E.M. had: they just couldn't decide which tracks to get rid of, so they just made longer and longer records. In this age where you can hardly give away music, let alone sell it, I think one of the ways to seduce the listener is to present them with a short piece of music. Everything is available, anyway; if you want to download it, you can find it. The record companies are just desperate to give away anything for free to lure people in. Or in my case, everything will come out 20 years later as part of a box set. You have a really good perspective on stuff later. Some of the things we've done…demos we've just finished off, things that I've had 20 years previously…I think we'll make this nice and to the point, the next album, and it will contain elements of the thing we recorded with John Edgington. But the whole thing is just sitting there in the vault; it's monstrous. I mean, not horrible, but there's piles of it. It's like a kind of Let It Be, but with good vibes. There's just cover versions and old things retaken and stuff done at parties and late night things with Nick and John and everybody. It's all fantastic but I don't think that will appear.

BE: Basically, I'll have to wait for the reissue of the Yep Roc material.

RH: Yes, I think. Find out who's going to reissue the Yep Roc material and what the bonus discs are, and if I'm still alive...you know, I don't even need to be alive. All I need to do is have recorded it.

BE: Being alive has never stopped any record label from releasing material.

RH: Well, you do better when you're gone, and I'm morbidly aware of that. But I am still alive, which limits my marketing potential but can't be helped.

BE: Well, I'll keep my fingers crossed you can rise above.

RH: Thank you. Anyway, it's good to talk to you again.

BE: Absolutely. As ever, I intend to see you on the upcoming tour, but I've got a two year old, so we'll see what happens.

RH: Oh, you'll see your two year old, that's what'll happen. But it doesn't matter. I'm sure we'll be around.

You can follow us on Twitter and Facebook for content updates. Also, sign up for our email list for weekly updates and check us out on Google+ as well.