With the temperature dropping, it's time to find someone to keep you warm. Find your hookups with our online dating guide!

With the temperature dropping, it's time to find someone to keep you warm. Find your hookups with our online dating guide!

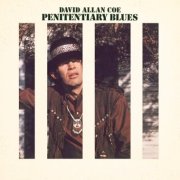

Penitentiary Blues

- Electropop

- 2005

- Buy the CD

Reviewed by Will Harris

()

Coe had his first brush with the law at the ripe old age of nine, setting the stage for the next twenty years, much of which was spent in custody; in fact, he spent most of his twenties in the Ohio State Penitentiary, which, if nothing else, did quite a lot to provide him with material for his first few albums. Despite not exactly cutting the figure of the late ‘60s definition of a country singer, with his wild hair, tattoos, and earring, Coe still went straight from prison to Nashville, reportedly living in a hearse that he parked outside of the Grand Ole Opry. Eventually, through the column of music writer Jack Hurst, Coe’s music caught the ear of indie label Plantation Records, who sprung Penitentiary Blues onto an unsuspecting public.

No, it wasn’t exactly what the country crowd was listening to at the time.

All that marijuana

Selling cocaine

Now they’re taking blood tests

From my heroin veins

Oh, baby, the things I used to do now

I was born to lose

Penitentiary blues

The title cut led off the album, so, from the get-go, listeners suspected they weren’t going to be in for an easy ride...and, yet, Coe added a dark sense of humor to the tracks. Even the song entitled “Death Row” was about a prisoner asking for his last meal, picking such culinary obscurities as “fried bat wings, over easy” and “the hind leg from a black giraffe cooked medium rare, not too greasy,“ in order to prolong the inevitable, and the piano-pounding “Cell #33” could almost be described as rollicking. (Imagining Jerry Lee Lewis covering the song is surprisingly easy.) It’s only the one true blues song, “Funeral Parlor Blues,” that’s totally serious; when the narrator sings of “going down to the funeral parlor / To see my baby one more time / Gotta take a shot of cocaine / ‘Fore I go out of my mind,” it’s clear how the phrase “a shot of courage” originated. The only non-Coe-composed song on the album is Hank Mills’s “Walkin’ Bum,” which was later covered to great effect by ex-Plimsoul Peter Case on his album, Peter Case Sings Like Hell.

The packaging of this reissue mimics that of the original, with a gatefold cover framing a photo such that he appears to be behind bars, and the booklet provides in-depth liner notes by respected music historian Colin Escott (“Good Rockin’ Tonight: Sun Records and the Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll”), as well as excerpts from Coe’s own book, “Ex-Convict,” which is sadly out of print. One would think some publisher would’ve taken advantage of the opportunity to re-release the volume in conjunction with this re-issue of Penitentiary Blues, but, if so, word of such has not yet reached the all-knowing World Wide Web.

Some have described this album as “redneck music, pure and simple,” but that’s not the case at all. Sure, Coe would have his redneck stage, going so far as to entitle an album Longhaired Redneck in 1976. This, however, is prison music, composed behind bars and recorded not long after getting out. It’s true and honest, drawn from personal experience.

If you doubt it, try listening to the album as you read through those excerpts from “Ex-Convict;” with lines like, “Don’t ever get in anyone’s face unless you are ready to die or kill to keep from dying,” you ought to be convinced right quick.

You can follow us on Twitter and Facebook for content updates. Also, sign up for our email list for weekly updates and check us out on Google+ as well.